“My dad worked at an affluent company that did not have to let workers go. My home was mostly unaffected because of the area we lived in. We were lucky. We are the story you hear about on the news. Others were not,” said New Orleans resident Molly Rossignol.

Rossignol, a college student in Louisiana, lived through the hurricane in 2005.

However, 15 years after landfall, recovery is still on the mind for those in certain areas of New Orleans, and this plea is being consistently ignored by the city.

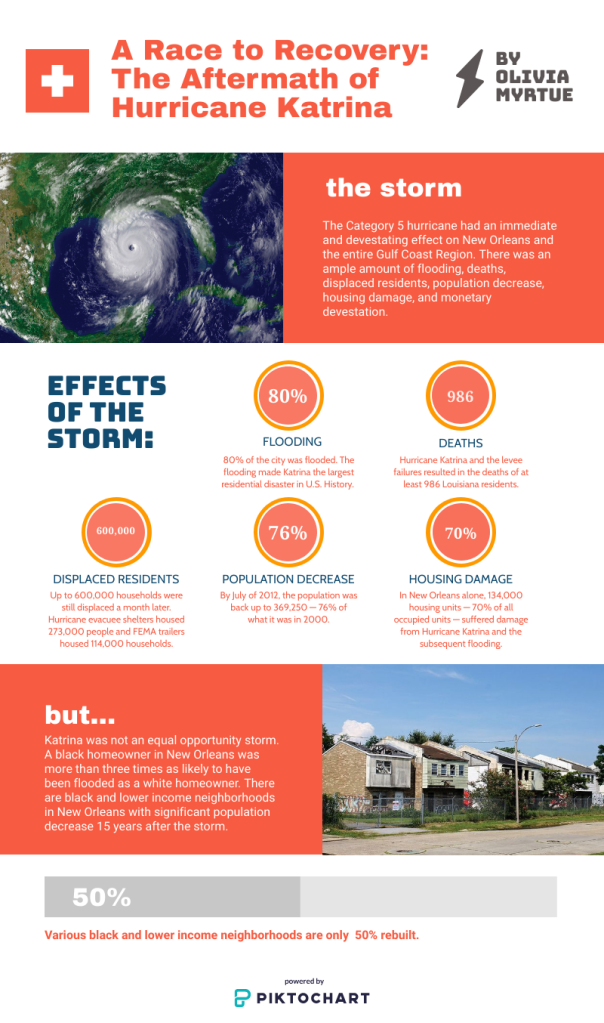

According to the Environmental and Energy Study Institute, many communities in New Orleans are still a work in progress. These communities are primarily lower income and black communities.

“When walking around New Orleans, it is easy to see the areas that have been rebuilt and the ones that have not,” said New Orleans resident Gracie Thomason.

Thomason was exploring the city with a friend when they wandered into the Lower Ninth Ward. She noted that this area was one that no one often sees or hears about when they think of New Orleans.

“When driving through this area, it is devastating to see the destruction that is still there after fifteen years. There are tons of homes that are still abandoned from the storm, and some are still marked with spray paint from when police searched the homes after the storm. Unlike wealthier areas like Lakewood, which have been entirely rebuilt, these areas are still facing devastating loss, and homes here are still in major flood areas,” said Thomason.

The institute also noted that although 90% of New Orleans’s pre-storm population is back and much of the city has been rebuilt, the Lower Ninth Ward and similar neighborhoods have not had anything close to the same amount of post-Katrina growth. In fact, these historically African American and low-income neighborhoods that boasted a 14,000-strong population in 2000 now hold way lower populations since Hurricane Katrina, as they were affected the most by the storm.

Not only were these areas affected the hardest by flooding from the storm, they also were ill-prepared. These neighborhoods were not classified by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to be floodplains, so residents did not have flood insurance. This led to a devastating monetary impact on top of all of the destruction.

After landfall, little pieces of aid that were coming into the city were going to the white, wealthy families to begin with. So, this is what the aftermath of Katrina became, a race to recovery with head-starts handed out to the privileged people, leaving everyone else behind in the flood.

“After Katrina caused widespread destruction on the Gulf Coast and flooded much of the city of New Orleans, it quickly became evident that most of the people remaining in the city were black. Many of these African Americans were from low-income neighborhoods. Many had no cars, no money, and no friends out of town to whom they could turn,” said the Journal of Blacks in Higher Education.

The journal noted that it was five days before significant federal or state help arrived for the tens of thousands of blacks who were marooned in the city, and a number of African-American political leaders charged that the response would have been far quicker had the victims been in the predominantly white cities of Palm Beach or Boca Raton.

Moreover, this recovery aid was not going to African Americans in the city, even though they were the ones who needed it the most. And because of environmental racism, many of the black neighborhoods in New Orleans were the ones the furthest below sea level and most susceptible to flooding.

“Katrina was not an equal opportunity storm. A black homeowner in New Orleans was more than three times as likely to have been flooded as a white homeowner. That wasn’t due to bad luck; because of racially discriminatory housing practices, the high-ground was taken by the time banks started loaning money to African Americans who wanted to buy a home,” said Gary Rivlin, a pulitzer-prize winning investigative reporter.

In other words, these black neighborhoods were in danger zones for flooding, and, when Katrina came, it was proven to be true that the people affected most were people of color.

“Hurricane Katrina was not about rich or poor, but about the unequal status of Black people in a land that espouses liberty and justice for all,” stated Fred Arthur Bonner in the Journal of Negro Education.

Bonner emphasized the ways in which race and socioeconomic status follow each other, especially in disasters like Katrina.

To this day, you can drive in historically black areas of New Orleans and still not see a single rebuilt home from the storm. These parts of New Orleans are parts that tourists and news vans rarely take time to see, yet they are still in dire need of aid from the storm.

The most shocking fact is that there are still neighborhoods that are only 50% rebuilt, and it has been 15 years since Katrina. New Orleans is not the comeback story we claim to be if our congressmen only focus on the rebuilding of the affluent, white neighborhoods and rarely take the time to venture to the parts of the city that still hold abandoned houses stained with flood water.

“I think about my own Katrina story and consistently think about how lucky I was. And then I see the stories about how much of a comeback story New Orleans is, and I think that is not right. We are not a comeback story if the only areas that have come back from the storm are white and wealthy. Our leaders need to step up and make real change in these areas,” said Rossignol.

If not now, then when?