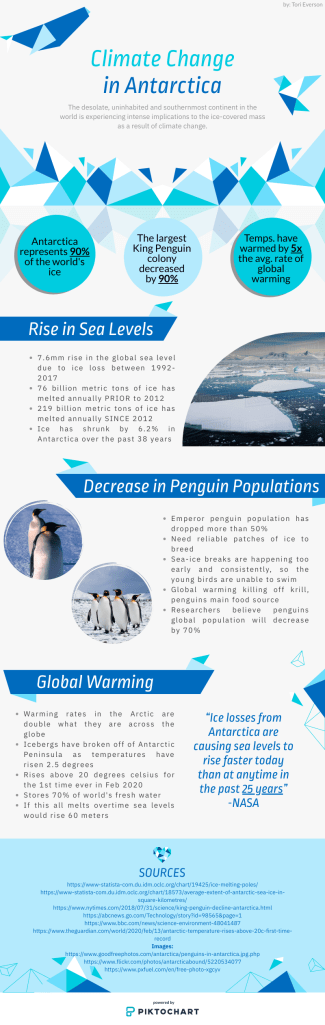

The surface temperature of Antarctica has warmed by more than 0.1 celsius per decade in the last 50 years. This is five times the mean rate of global warming, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The Antarctic Peninsula is subjected to the most rapidly warming parts of the planet.

Scientists have noted that the Antarctic Circumpolar Current is warming at a greater rate than the ocean as a whole. This is one of the main reasons why climate scientists have directed their attention to studying climate change in Antarctica to predict the future implications and to inform policy makers on these growing numbers.

This change in temperature has caused the wildlife in Antarctica to dramatically decrease. This means the penguin population. More specifically, the emperor penguin colony in Halley Bay lost more than 10,000 chicks in 2016 and today has not recovered.

“The penguins have nowhere to live and get food. It is becoming a huge problem due to the sea levels rising,” Munns said.

This was Antarctica’s second largest colony. Penguins are extremely vulnerable to warm temperatures and wind. Halley Bay faced a stormy year in 2016 with tumultuous winds and record-low sea ice.

This is only one implication of climate change that is apparent in Antarctica and is raising questions on long-term concerns for this block of ice surrounded by seawater. Scientists have used this case study as a projection of drastic declines by the end of the century in the emperor penguin populations as a result of climate change.

Hannah Stanley a sophomore at the University of Denver is a biology major, and is extremely passionate on the current trends of climate change.

“I think it is interesting that people think climate change is fake and don’t believe it is actually happening. I feel people need to know more about it. People should care about climate change more because it affects their health, their future and the whole planet,” Stanley said.

It is predicted to be a 30 percent worldwide drop in penguin populations in the coming decades, according to Stephanie Jenovrier, an associate researcher at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Jay Lemery professor of emergency medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine spoke at the University of Denver on climate change and the impacts on human health. Lemery made notes on how analyzing the ice cores in Antarctica and Iceland is telling on the rate of climate changes.

Doctor Julie Morris, professor at the University of Denver in the department of biological sciences, attended the lecture on climate change and is an advocate for ensuring students are aware of the science behind climate change, and how it is a major issue.

“We are in a state where we cannot predict what is going to happen,” Professor Morris said.

These concerns connect directly with the increase in frequency of extreme climate related events especially with the unpredictable alteration of the sea ice cover. These unprecedented events, such as heat waves, precipitation and storms disrupted the Adélie penguins population. They did not respond well as the population had to go through more intense foraging techniques for food and altered the community dynamic.

“There is a social cost to this and a major issue of unpredictability,” Professor Morris said.

Climate change in Antarctica has been a major topic of conversation in the Paris Agreement objectives. The Paris Agreement made a goal to account for all of the known emperor penguin colonies in the climate change scenario meetings. The main goal was to help the penguins through a climate-dependent-metapopulation model, so that the penguins could mitigate climate effects through movement and habitat selection.

“I think climate change in Antarctica is telling for us worldwide because things are building on top of each other and everything is connected. Global warming is taking away home life from penguins, polar bears and Arctic life,” Bergen Sullivan, a sophomore at the University of Denver, said.

Human-caused climate change or otherwise known as global warming is the main cause for the dwindling ice caps in West Antarctica. This happens as the amount of greenhouse gases increases, and then the maritime air masses absorb the warmth surrounded by the sea and transfer this heat from the ocean and push it inland.

“If glaciers are melting, then the water is rising and eventually getting warm and that is impacting marine life, and can eventually become an algae bloom which would impact fishing and so much more which would in the end impact us,” Sullivan said.

The polar regions like Antarctica are great for detecting the alterations of global warming over time. This is important since Antarctica holds 90 percent of all of the ice on the planet, so this continent is a vital indicator in the future implications of climate change.

“There is a certain number of inches that the water level can rise per year before it is too late, and I am concerned that no one is talking about that,” Stanley said.

The melting of glaciers, ice shelves and the sea ice from 1993-2003 has contributed to a 0.2mm per year sea-level rise and has only been increasing, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Scientists have projected that the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere will rise and eventually warm the interior of the continent. The Peninsula and Antarctica’s coastline will experience the worst effects of climate change.

“People are really unaware of how many consequences there are of climate change and I think that is part of the issue because nothing is being done to change it,” Stanley said.